If you want to learn data science, you’re going to have to learn statistics.

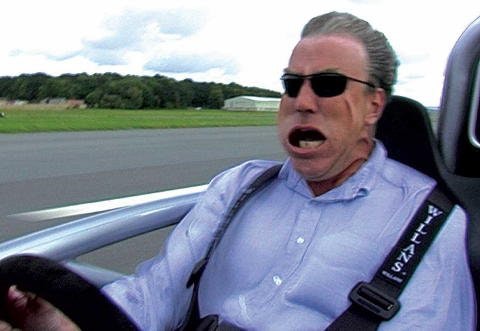

This was something that was never outright said to me (or perhaps my brain deemed it less important than Anchorman quotes and price fluctuations of Oreos), but was quickly learned over the course of a few short weeks in the Flatiron bootcamp. Now, I consider myself to be good at “exact math” as I call it–calculus and linear algebra, etc.–but it was always in the back of my mind that I was marching into unknown territory, and so I made a conscious decision to fight the urge to fix and eliminate all statistical error as we went along. One thing that always helps me sally forth, I’ve found, is an understanding of why we’re doing what we’re doing. As long as I had a tangible grasp on the reasoning and applications behind various statistical modeling and hypothesis testing, for example, I could endure the struggle. But “the only good pace is a suicidal pace” rang true for me, and I often had to set aside my desire for tangibility in favor of staying buckled in on the racetrack.

Unfortunately for me, and for other aspiring data science students, it’s often difficult, especially in the feed-us-with-a-firehose environment of most bootcamp-type environments, to find the time to come back down to Earth and really dig into application. I had this same difficulty when trying to learn statistical analysis, especially when trying to connect manipulation of data and testing of hypotheses with real, actionable business ideas. It was made more difficult, at least to me, by the consistent use of fake data to teach relevant concepts. Now, don’t get me wrong, I understand the need to use fake data in order to create teachable moments in a vacuum, but there’s still an underlying feeling of disconnect and worry, and it always leads to a sort of learned, shaky confidence at my future ability to apply it to Actual Data (patent pending).

Nevertheless, I trudged forth into the made-up Northwind database to put my newly minted statistical analysis skills to the (hypothesis) test.

Types of Hypothesis Tests (And What They Tell Us)

It’s easy to get caught up in the sheer volume of different hypothesis tests. Just to name a few, we’ve got T-tests, ANOVA, Tukey range test, Mann-Whitney, Kruskal-Wallis, and Bon-Jovi (okay, maybe not that one). Each one has its own conditions for use, predicated on things such as normality of distributions, homoskedasticity, etc. Fortuitously, we can get around most of these (admittedly stretchy) assumptions by having large sample sizes. I’ll be honest, even writing that last sentence feels like cheating at math, but we’re data scientists now, and the laws of math are ours.

Before we decide how to test our hypothesis, however, we need a hypothesis to test. Enter my best friend, the Null Hypothesis. This is a fancy, shorthand way of saying, “Okay, we’ve got all this data, but there’s literally no measurable difference between one facet and another facet, and anyone who says otherwise is lying”. With this in the right hand, and the structure of the data in the left, we can put them together to arrive at the appropriate method for testing.

T-testing (And Others)

Say we have one sample of data and we’re trying to figure out if it came from a population with a given mean. This test will return the probability that this is true. If we have two samples of data, a variation of this will give the probability that the two samples came from the same population. This is just a fancy way of saying, “Is one set of data different from another set of data?” or “Is one set of data different from known properties of the population?” If we get a low P-value, the samples likely don’t come from the same population.

For my work with the Northwind database, I used the non-parametric (fancy-speak for “let’s use the median instead of the mean because our data is so skewed it looks like a graph of MC Hammer’s career”) version of T-testing called Mann-Whitney, located in SciPy. In checking if the quantity of product in a particular sales order varied based on the type of discount offered, I first needed to see if any discount mattered. Fortunately, it only takes a few lines of code:

import scipy.stats as stats

df['discounted'] = np.where(df['discount']==0.00,0,1)

df.head()

grp0 = df.groupby('discounted').get_group(0)['quantity']

grp1 = df.groupby('discounted').get_group(1)['quantity']

stats.mannwhitneyu(grp0, grp1, alternative='two-sided')

We run a two-sided test to account for customers who might order less product if offered a discount. It’s a more conservative approach, to be sure, but our P-value ends up being low enough that it doesn’t matter. Our null hypothesis is rejected, and we can confidently say that discount has a statistically significant effect on quantity of product in an order. This might have made intuitive sense from the beginning, but now we have mathematical evidence backing us.

Now that we know that discount has an effect, we use Tukey’s test, located in statsmodels, to find out which ones have a significant effect.

import statsmodels.api as sms

data = df['quantity'].values

labels = df['discount'].values

model = sms.stats.multicomp.pairwise_tukeyhsd(data, labels)

model.summary()

This spits out a table containing the differences between each of the discount levels. In the case of the Northwind database, there are ten discount levels ranging from 1% to 25% off. Tukey’s test tells us that only four of these have any real effect on quantity of product ordered: 5%, 15%, 20%, and 25%. Tukey also tells us that none of these four discounts have any higher of an effect than the other ones, which is interesting by itself.

ANOVA (Analysis of Variance)

When comparing two sets of data against each other, or when comparing one set of data against a population with known parameters, a simple 1- or 2-sample T-test is fine. But when we have multiple sets of data being compared against each other, it does more harm than good to use multiple T-tests. For example, when performing one T-test, the probability of getting a correct result is 1-p = 0.95, or 95%. When running a second T-test stacked on top, the chance of getting a correct result is 0.95 * 0.95, or 90.25%. This probability is further decreased the larger the number of T-tests we perform.

The solution to this problem is using Analysis of Variance, or ANOVA for short. This tests the probability that all of the samples have the same mean, but again, it doesn’t say which one(s) is/are different, if any. This can also be used in tandem with Tukey’s test, which we ran in the previous example.

For my work with the Northwind database, I tried seeing if order sizes differed based on the time of the year. I split the data into quarters (we’re talking fiscal quarters here) and plugged each group of data into the f_oneway function built into SciPy:

#adding a column specifying the quarter of the year the order took place

df['orderdate'] = pd.to_datetime(df['orderdate'], format='%Y/%m/%d')

df['quarter'] = df['orderdate'].dt.to_period("q")

df['quarter'] = df.apply(lambda row: int(str(row['quarter'])[-1]), axis=1)

#splitting data into groups by quarter

grp0 = df.groupby('quarter').get_group(1)['quantity']

grp1 = df.groupby('quarter').get_group(2)['quantity']

grp2 = df.groupby('quarter').get_group(3)['quantity']

grp3 = df.groupby('quarter').get_group(4)['quantity']

from scipy.stats import f_oneway

f_oneway(grp0,grp1,grp2,grp3)

Again, we can run Tukey’s test to spit out which quarter(s) had different sales quantities.

Putting Them Together

In this post, I’ve outlined a few techniques for testing a couple of hypotheses and illustrated the different approaches to both of them. Despite these differences in particular, and the somewhat nebulous nature of hypothesis testing in general, our confidence levels remain high, and the information gained can be put together quite cleanly when readying a presentation to the boardroom. In the illustrated Northwind database examples, I came up with two questions to ask that, I’ll be honest, came from two different places in my mind. It was only after I was done scything the weeds that I looked back at my work and realized I was answering one question, “How do we increase sales?”, in two different ways.

Could it have helped me to keep that single, dense question on a sticky note attached to my computer monitor? Of course. I’d rather have one sticky note than thirteen trillion different trains of thought, all popping in and out of existence like quantum foam. Had I kept all those on sticky notes, things would have quickly gotten out of hand.

I guess if nothing else is taken from this post, understand that real-world application is something I kept trying to find after learning something, rather than looking for business case uses for a concept while learning it. It’s worth remembering, after all, that we create hammers because we have nails; let’s not look for nails simply because we have a hammer.